|

| The Polymath, a rare species. |

The

history of science, from the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians through the Renaissance and Age of Enlightenment in Europe to the modern science of the last century and this, has been filled with remarkable people and great minds

. The full list spans millenia and continents. The scientists of those early days were

polymaths of the highest calibre. For example

Aristotle wrote on subjects as diverse as physics, metaphysics, poetry, theatre, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology. Even in the 18th century

Newton was an authority on, mathematics, astronomy, natural philosophy, alchemy, and theology. Those days of Jack of all trades scientists are, sadly, no more.

The logical supposition may be that scientists aren't as brainy as they once were. While clearly those names that have lived on through the ages were people of astonishing intellect, there are still plenty of erudite researchers around today. The real issue is that scientific knowledge has expanded so rapidly it is now impossible to be an expert on everything. In fact you realise that the more you become an expert on a subject, the less you know about it.

Initially science was divided into

Natural and Social science. Natural science then split into Biology, Chemistry and Physics, with the era of real scientific specialisation dating to the beginning of the 19th century when research became professionalised and institutionalised. Areas from each of these three disciplines have been in vogue at different times throughout recent history.

|

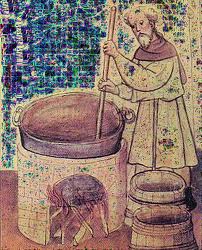

| The Bazalgette's latest sewer offering. |

The

industrial revolution of the 18th century was a time remembered for astonishing engineering feats such as

Brunel's Great Eastern and

Bazalgette's London sewers. However, these endeavours were underpinned by advances in chemistry including the understanding of combustion, advances in building materials, the production of new synthetic dyes and detergents for the textile industry as well as mass production of fertilisers and drugs to keep the millions of workers living in urban squalor alive. Coupled with fantastical public chemistry demonstrations, this enabled chemists, such as

Humphrey Davy, to rise to the top of scientific and social celebrity status in London.

Due to our fascination with the human condition and the fact that these people can make us live longer, there have, throughout history, been well know practitioners of medicine. For example, the elephant man Joseph Merrick's physician

Dr. Frederick Treves and modern day TV personalities such as

Prof. Robert Winston. The biological sciences only really captured the public imagination in the latter half of the 20th century, coinciding with global travel and the advent of television. Darwin's studies or even the elucidation of the structure of DNA by

Crick & Watson were discoveries which were quite esoteric in their nature. Natural history on the other hand was striking and generally accessible making presenters such as David Attenborough household names.

|

| Prof. Cox's default middle distance gaze. |

Physics has had an image of unfathomable people carrying out incomprehensible work. This has all changed recently with still incomprehensible but sufficiently mind-blowing work, such as the search for the Higgs Boson in the

Large Hadron Collider and

Neutrinos traveling faster than the speed of light, being presented by the entertaining and, in some people's eyes, photogenic

Prof. Brian Cox. Physics is now cool with the general public genuinely interested in trying to understand how it works. It is too early to tell whether physics will go the way of flared trousers or

hyper-colour t-shirts, but it would certainly be the Christmas No.1 of science this year. More importantly, this interest offers an opportunity for public engagement in all areas of science and means that even researchers in lab coats and safety specs working in windowless labs can

D:ream that things can only get better for their chosen career.